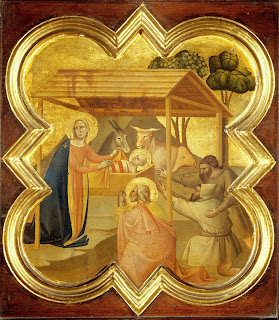

Image: Taddeo Gaddi, "Adoration of the Shepherds," c. 1330-1335.

If we run our fingers through the wolly textures of the Chester Shepherds’ Play, we are likely to be caught by a few matted snarls. Landscape, hunger, animality, agriculture, economy, and religion: these threads combine to create a thickly interwoven cloth of meaning. It is a play that is deeply embedded in scenery of Cheshire, Lancashire, and the Welsh marches and deeply connected to the social relations of the sixteenth century; the relationship of text and context is indivisible. As with the best comedies among the Cycle plays, the Chester Shepherds’ Play is enlivened by a beastly energy, but we should remember that this same fleshliness also underpins the play’s contexts. The aim of this paper is to consider how the Chester Shepherds’ Play participates in a discourse that Latour would say “is not a world unto itself but a population of actants that mix with things as well as with societies, uphold the former and latter alike, and hold on to them both.” The play invokes the enclosure movement to dramatize the fraught relationship between the religious and economic institutions that framed Chester’s performance spaces. The very actants at the center of the play’s critique – the animals, the food, the bodies of laborers – sustain the livelihood of the rural producers and sustains the bodies of performer, commons, and countryman alike, demonstrating how all are bound in an ecological relationship. Whether harmony can be found will be considered in the conclusion.

The drastic reconfiguration of the pastoral landscape in sixteenth-century England can be described in terms of the shifting network of animal energy: livestock and laborers, food producers and consumers all of which circulated through the markets that served as the play’s performance spaces. Positioned at the intersection of urban and rural life, the market reminded all consumers and producers that while civic and ecclesiastic authority can be compartmentalized into counties and bishoprics, the food economy bound everyone and everything together. The market was both city hall and cathedral for the entire foodshed and all of its inhabitants. Even without the occasional performance of plays or civic ceremonies, markets were already ritualized performance spaces that spoke to broad audiences. As Jean-Christophe Agnew argues, the market’s “customary location … near places of worship, the seasonal cycle of festive celebration, and the eventual development of religious processional ... are all testimonial to the importance of ceremonial and redistributive gestures to the legitimation of class power and authority.” Markets were and are still sites of confluence; with each market bell, cultural forces and economic factors ran together as the basic material concerns of the community were negotiated, perhaps resolved. The marketplace made for a readymade stage to communicate to rural and urban audiences alike.

We should remember that the privatization of agriculture was coupled with the secularization of the land. The Kentish ballad “Now A Dayes” calls attention to this conversion and the coeval spiritual and economic unrest of the early sixteenth-century: “The townes go down, the land decayes; / Off cornefeyleds, playne layes; / Gret men makithe now a days / A shepecott in the church. / The places that we Right holy call, / Ordeyned ffor christyan buriall / Off them to make an ox stall / thes men be wonders wyse. / Commons to close and kepe; / Poor folk for bred [to] cry & wepe; / Towns pulled downe to pastur shepe: / this ys the new gyse!” The new economic structures convert the land from spiritual space to economic space, transforming graveyards into agricultural buildings. Church land is enclosed not for anchorites but for sheep.

The Shepherds’ Play reclaims the secular spaces and reendows them with spiritual purpose. By invoking the anchoritic profession in its closing lines, the play asked its sixteenth-century audience to think on the relationship between the new connotations of land enclosure as they related to the connotations of spiritual enclosure. Where church institutions had been an integral part of the rural landscape and a critical managing partner in the agricultural economy, new large-scale producers had taken over and further segmented the foodshed. The Shepherds’ Play as performed to popular acclaim in the Beast Market and the Corn Market is the city of Chester’s protest against the shifting market forces by attempting to bridge the widening maw between market and church. As the wagons passed through sites of economic and religious significance, the performance route traced an itinerary for an interlaced economic and spiritual development: as the town clerk, William Newhall, wrote in 1531-32, Chester performed the Whitsun Plays “not only for the augmentation and increase of the holy and catholick faith of our savior Jesu Christe and to exort the mindes of comon people to good devotion and holsome doctrine therof, but also for the comon welth and prosperity of this citty.”

Central to the play’s critique are the wares of the market stalls. The feast scene of the Shepherds’ Play is heavily invested in the local food economy: the shepherds bring “butter that bought was in Blacon,’ “ale of Halton,” and a “jannock of Lancastershyre” (7.115, 117, 120): the geography of the play represents the sizable foodshed that fed Chester’s markets. This should be seen in light of the development of the macroeconomic forces that replaced the close-circuited nucleated economies of manorial farms with an increasingly stratified market economy. The variety and quantity of food that the shepherds consume gives some hint of the number of food producers on whom the people depend. The shepherds’ feast does not suggest self-containment, as some critics have alleged, but the vast interconnectedness of the Cestrian food economy. With the growth of monoculture and product specialization, the distribution of foodstuff had to be accomplished at the marketplace. The marketplace coordinated the foodshed’s network of producers and consumers (parties that are never mutually exclusive), even as it created space for competition. As Christopher Dyer shows, cattle fattened on the Cheshire heath were sold for higher prices in London than in Chester. Cheshire cheese became internationally famous. But the national demand for Cheshire foodstuffs meant that farms were not raising corn and wheat for the local market. At issue, then, is the commercial drama between rural producer and urban consumer replayed each and every week.

The Whitsun plays’ pertinence to this dual audience is made explicit in the post-Reformation Banns that would announce a performance of the plays: “By Craftes men and meane men these Pageanntes are playde / And to Commons & Countrymen accustomablye before.” These Banns do not suggest a neat symmetry between city and play, but triangulate the asymmetric economic relationship between performers, city residents, and residents of the countryside. The performance of the Chester cycle was part and parcel of the exchange between Chester’s urban consumers and the agricultural producers of Cheshire and environs that already was occurring in the city’s marketplaces. It is this context for the English Shepherds’ Plays which I think have been underappreciated. Although the social and religious transgressions of the Chester feast scene (as well as the Towneley Prima Pastorum’s feast) have received much critical attention, the play’s relationship to the Tudor enclosure movement has largely been ignored. The setting on the secular, contemporary heath represents a desacralized, commercial environment populated by shepherds pitted against each other for food, wages, and self-respect. As the play unfolds, the shepherds ultimately denounce their own lifestyle as unsustainable and call for a resacralization of the pastoral economy.

Agricultural manuals and anti-enclosure pamphlets moralize the division between consumer and producer. The demand for profits was supplanting the traditional, idealized role of the farmer in the foodshed – to provide for family and community. Like Thomas More’s sheep in Utopia, Chester’s shepherds have become carnivorous. Beginning the meal, Hankeyn declares: “My sotchell to shake out / to sheppardes am I not ashamed. / And this tonge pared rownd aboute / with my teeth yt shalbe atamed” (7.133-136). This sudden appetite for flesh violates the proper hierarchy of the economic food chain: producers are also becoming consumers, precipitating both a moral and an economic crisis. The new modus operandum of the agrarian economy, the pamphlets allege, is to satisfy the self first, without regard for equity, fairness, and commensality. The agricultural producers are no longer “meek and tame,” but as More says, they have developed a hunger for the food (or the profit) they produce. It is unnatural for the sheep to take from rather than give to their community. Hankeyn’s ravenous appetite resembles that of the Towneley Prima Pastorum’s Gyb who eats his own sheep after they have died of rot under his care: “Both befe, and moton / Of an ewe that was roton / (Good mete for a glotton); / Ete of this store” (12:318-321). The shepherds of Chester and Towneley have resolved not to till the soil and provide for the community, but to consume produce at a voracious pace.

The comedic depiction of “Shepperde[s] poore of base and lowe degree,” as they are referred to the post-Reformation Banns, correlates with these contemporary urban attitudes regarding rural farming populations. It is worth noting that in the pre-Reformation Banns, the shepherds are not called “poore of base and lowe degree,” but are presented with “full good cheer” and with “right good wyll.” This suggests either the content of the play changed over time to emphasize the shepherds’ newly sordid character or negative attitudes toward the shepherds and shepherding developed as the enclosure movement progressed.

Using the shepherds to depict the destabilization of the local foodshed, the play castigates the market forces driving rural poverty. The shepherds feast while their servant boy, Trowle, labors out of their view among the animals in the fields, insisting they are not “ashamed” of their voracious appetites even as they knowingly partake in idleness and sensual pleasure (7.80, 7.134). Trowle reacts against this self-interested behavior. While on the hill above him the three shepherds enjoy a feast alienated from the labor that produced the meat, Trowle commiserates with the animals below: in the darkness of the countryside he feels the continuity of blood and bone with his sheep and his chief companion, his dog Dottynoll. The play asks its audience to think of the producers and animal products that arrive in the city markets each week not as abstract concepts but as animated bodies participating in the network of social relations.

At a time when the problems of enclosure and engrossment were compromising the economic health of cities like Chester, the Shepherds’ Play reflects on the local region's changing economic conditions. For all that Chester consumers depended on foodstuffs and other animal products from the countryside, the city markets maintained an uneasy relationship with local producers. Product specialization led to price inflation of underclass staples and increased reliance on markets for foodstuffs. That the shepherds, participants in the new economic structure, enjoy a gluttonous meal while local food prices remained high, would have made the feast seem even more egregious to its audience. The food, the shepherds believe, elevates them above their station: Tudd terms the meal “a noble supper” and Hankeyn describes his meal as proper “meate for a knight” (7.124, 239). The shepherds are feigning wealth here; their nobility is either imagined or aspirational. Hence their transgressions of class boundaries is an example of what Norma Kroll calls, in the context of the Towneley Second Shepherds’ Play, a “hierarchical fantasy.”

Trowle separates himself from the other shepherds with an opening monologue laden with references to the hierarchies of agricultural economics. Entrenched on his own plot of land, he refuses to do the work assigned by his slothful masters, linking them to the nobility: “For kinge ne duke, by this daye, / ryse I will not – but take my rest here” (7.186-187). Trowle's belligerence gestures toward the Tudor enclosure movement. Trowle's plight resembles the situation of tenant farmers under threat of displacement or eviction by enclosure. Hankeyn, Harvye, and Tudd’s separation from labor also alienates them from the “blood and bonne” of the sheep they are consuming, embodying a growing division between consumer and producer.

A wrestling match ensues in which Trowle shames Hankeyn, Harvye, and Tudd and reinstates social order. Trowle joins the moralists of the pamphlet debate in rebuking the immoral appetites of shepherds and agricultural producers large and small. They all discover together that “true” solace is not found in caloric intake, but in spiritual joy. It is at this moment that the angel appears. Although at first they mistake they mistake the angel for a sheep-rustler or a rival landlord threatening engrossment (telling comments in of themselves) the angel instead summons them away from Chester and toward Bethlehem. There they continue to take their newfound pleasure in anti-materiality, or rather in a spiritualized flesh that suggests a sacred alternative to the secular continuity of blood and bone. Unlike the anti-communion of eating sheep that drives the shepherds apart in the first half of the play, the shepherds’ take communion upon coming into contact with Christ’s body: the shepherds’ role as witnesses is essential as it reestablishes the unity of their boys’ club and disperses all prior concerns regarding wives, work, wages, and wethers. In contrast with the divisiveness of pulling apart animal bodies, sharing the common image of Christ’s body brings the shepherds together. They are moved from a desire to consume to a desire to love. Rather than taming flesh with their teeth, the mouth becomes an organ for love and humility. For Trowle, the emphasis has shifted from material solace that fills the stomach to spiritual solace that fills his heart: “Solace nowe to see this / byldes in my brest blys: / never after to do amys, / thinge that him loth ys” (7.492-95). Thus, Trowle also renounces sin and pledges to be on his best behavior. This oath sets an example for the shepherds in the play and, perhaps, sets the standard for the resacralization of pastoral husbandry. The (re)discovery of spiritual solace seems especially transformative for the shepherds, given their relationship with animals. Where the shepherds would expect to find animals (in the “cratch,” that is, a “rack or crib to hold fodder for horses and cattle in a stable or cowshed” [OED]) they instead find Christ. Neither Dottynoll the dog nor the sheep who played prominent roles in the first half of the play are transported to Bethlehem. All animals disappear from the text once Christ arrives on stage. The nativity offers an alternative to the unnatural deviance of More’s carnivorous sheep. Instead of becoming devourers, the shepherds might once again be relegated to the lowest ladder of the food chain.

Kissing the talismanic body of baby Jesus wipes away all of the shepherds’ vices. Set on the path to righteousness, Harvye even surrenders his drinking flask and his spoon, renouncing intoxication and gluttony: “Loe, sonne, I bringe thee a flackett. / Therby hanges a spoone / for to eat thy pottage with at noone, / as I myselfe full oftetymes have donne” (7.571-74). Harvye’s offering could be seen not as an act of generosity, but as a recognition of his own moral failings. By giving up his spoon, Harvye implies that his hunger has also disappeared, that from now on he has no need of an eating utensil. The other shepherds' offerings to Christ are so laughably simple that their poverty becomes humorous; all Trowle has to give is “payre of [his] wyves ould hose” (7.591). The humor indemnifies poverty as a quality of rural producers: the play argues that shepherds should not be status-seekers, they should not pursue material wealth, they should be, as More would have it, poor, meek, and tame. The willingness of the shepherds to make an offering to Christ, even though they do not really have anything to give, promotes a false harmony among haves and have-nots. The adoration of the shepherds depends on an ideology of deference to the social hierarchy and self-sacrifice even when stricken by poverty.

By the end of the Chester Shepherds’ Play, the four shepherds have shed their material concerns and have been reconciled with each other. They give up herding sheep and become evangelists: Although still poor and now jobless, the shepherds resolve to become anchorites and hermits, rather than give in to illicit behavior: The shepherds have moved from a covetousness of material things that divided them to a physical embrace that unites them. As hermits and anchorites, they would also be adopting a diet that was chiefly vegetarian, reestablishing the proper place of rural laborers in the foodshed. Having disavowed carnivorous agribusiness the Shepherds’ Play rejects secular enclosure in favor of sacred enclosure. And yet this spiritual growth is an imaginary resolution of a real problem. In a play dominated by material concerns, the shepherds cannot arrive at an economic solution and so they embark on spiritual careers outmoded by the Henrician reformation. This imagining attempts to narrate a swirling and irresolvable problem: as the markets, the sheep, the land are being pulled into the future, the play attempts to pull the audience back in time, toward Bethlehem and a sacred pastoral economy that never truly existed or only ever existed in discourse. The pessimist in me might say that the play only provides an opiatic answer to the structural problems of Chester's market economy since the shepherds' new careers are as untenable as their old ones. Post-Reformation spiritual enclosure does not safeguard anchors and hermits, just as Chester's markets do not attend to the needs of agricultural laborers. But the play does give its audience pause, allowing the audience to consider the place of the two institutions to either side of the wagon stage and their role in the newly emergent social relations and their role in shaping the future of the city.

1 Latour, Bruno. We Have Never Been Modern. Trans. Catherine Porter. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1993), P. 91

2 Jean-Christophe Agnew, Worlds Apart: The Market and the Theater in Anglo-American Thought, 1550-1750 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986), p. 26.

3 Quoted in David Mills, “‘None had the like nor the like darste set out’: the City of Chester and its Mystery cycle,” in Staging the Chester Cycle, ed., David Mills (Leeds: The University of Leeds School of English, Moxon Press, 1985), pp. 1-16, 4.

4 REED: Cheshire, 2 vols., eds., Elizabeth Baldwin, Lawrence M. Clopper, and David Mills (Toronto, ON: The British Library and University of Toronto Press, 2007), ll. 21-22.

5 REED: Cheshire, p. 336, ll. 17.

6 Cited in R.M. Lumiansky and David Mills, The Chester Mystery Cycle: Essays and Documents (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1983), p. 279.

7 Norma Kroll, “The Towneley and Chester Plays of the Shepherds: The Dynamic Interweaving of Power, Conflict, and Destiny,” Studies in Philology 100.3 (2003): 315-345, 333.